Freedom Fighters

Apr. 19th, 2025 01:05 pmSince ancient times, mankind has been preoccupied by a quest for “freedom”. Even in today’s somewhat enlightened society, safeguarding our “freedom” is an almost daily topic of conversation.

But I wonder how many of us have ever made the effort to formulate in words exactly what that term means to us. And if you don’t know what freedom means, how can you possibly successfully attain it?

For me, freedom has three main components: choice, independence, and ethics.

First is the freedom to choose between alternatives. Where a man has no choice to make, there is no freedom.

And to be truly free, that choice must be largely independent of external influence or coercion. A man who is coerced or misinformed is not able to freely choose.

And finally, “freedom” has no meaning unless a person can make decisions based upon the values and beliefs that he holds as the product of his upbringing, education, life experiences, emotional makeup, and philosophy.

As a bonus aside, I’ll assert here that a person’s values are most often a uniquely individual balance between benefit to oneself and benefit to others, where the latter category might be further subdivided into one’s “in-group/family” and “outsiders/others”, however broadly or narrowly one chooses to make that distinction.

So that’s my operative definition of personal freedom; now let’s consider whether we do a good job attaining it…

We humans like to think of ourselves as complex, multifaceted, and diverse, as the pinnacle of evolution, and imbued unique capacities of intellect, free will, discretion, morality, and freedom of choice.

How ironic then that, across all cultures and times, the overwhelming majority of human behavior can be reduced to two very simple principles:

- Get more of the sensations that we perceive as pleasurable, and

- Get rid of the sensations that we perceive as unpleasant.

This two-line algorithm is not only sufficient to describe almost all human behavior, but that of nearly all animal life, down the simplest amoebae and paramecia. If it’s pleasant, move toward it; if it’s unpleasant, run away from it. It’s poignantly emblematic that the Declaration of Independence, one of mankind’s most cherished documents, proclaims “the pursuit of happiness” as a vital and basic “unalienable right” of all men.

What does it say about our vaunted sense of freedom and individuality if 99% of all human thought, feelings, and behavior can be boiled down to a ludicrously simple two-line program, the exact same one used by the most tiny, primitive unicellular organisms? Where is freedom to be found in slavishly obeying that biological imperative?

Here is where the Buddhist in the audience has something to contribute.

Without judging anyone’s individual spiritual practices, I would assert that Buddhism is not fundamentally about stress relief, quiescing our thinking, blissing out, self-improvement, earning merit for future lives, extraordinary experiences, psychic abilities, or deconstructing the self. Those things may or may not happen along the way, but I think that the core goal of the Buddhist path is breaking free of our instinctual programming by first understanding that we habitually live under a false illusion of freedom, then gradually learning how to find genuine freedom by ensuring that our thoughts, speech, and actions are driven by conscious, values-driven choices, rather than never-questioned blind reactivity and maladaptive habit patterns.

Realizing that pleasure and discomfort are the central drivers of our biological programming, the principal line of inquiry for Buddhists has been cultivating a more skillful and beneficial relationship to these influences. A key tenet is the principle of dependent arising, which describes the chain of cause and effect that explains how our relationship to desire creates our experience of dissatisfaction. My distillation of it goes:

- Because we are alive, we have senses.

- Because we have senses, we experience contact with sensory objects.

- Because we experience contact with sensory objects, we experience sensations. These sensations are immediately perceived as pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral at a pre-verbal, instinctual level. Let’s call that the sensations’ “feeling tone”.

- Because our perceptions produce these low-level feeling tones, we instinctually relate to the pleasant ones with desire, the unpleasant ones with aversion, and are mostly disinterested in the neutral ones.

- When our desires and aversions arise, we react with craving and need, becoming entangled and increasingly attached to having things be a certain way in order for us to be happy.

- Because of our attachment to things being a particular way, in a world where we control very little and where change is inevitable, we suffer when our needs and desires are not met, and even when our desires are fulfilled, we become anxious knowing that it’s only temporarily.

This is the sequence of events that leads to our experience of dissatisfaction, stress, anxiety, suffering, and unhappiness.

Of course, if dependent arising were an immutable progression, it wouldn’t be of any practical value in our quest for freedom. But there’s one key step where — with sufficient mindfulness, wise intentions, and skill built up through patient practice – we can pry open a tiny window in this sequence of events and grasp our one opportunity to consciously choose a different response.

And that window of opportunity presents itself in how we relate to our sensations. It’s telling that, looking back on what I’ve written above, aside from “pleasure”, the other word that appears in both my two-statement definition of human behavior and the Buddhist principle of dependent arising is “sensations”.

A Buddhist would say that the only place where we have the opportunity to influence our unrealistic expectations is found in how we relate to our sensations. If we can see our perceptions clearly and in real-time, as well as the pleasant/unpleasant/neutral feeling tones that they evoke, we can wake up from our unexamined habit of letting those feeling tones blossom into the reactive craving and aversion that drives most of our subsequent thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. In each moment, if we can bring mindfulness to our sensations and our reactions to them, we can consciously choose to respond in a way that is less compulsive, less harmful to ourselves and others, and better informed by our values.

When it doesn’t harm ourselves or others, pleasure is a vital part of living a fulfilling life. However, our dysfunctional habit of blindly following pleasure and running away from discomfort needs to be balanced by wise intentions like purpose, mission, and ethical values that are more complex but also more advanced in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. In this sense, the traditional Buddhist monastic way of life may go a bit too far in its inclination toward banishing or vilifying pleasure, rather than seeking a middle way that allows one to wisely examine, engage, practice with, and potentially master one’s relationship to pleasure and aversion.

Note that this isn’t the same as saying that “life is just suffering” or that one has to avoid pleasure and resign oneself to pain. What I’m saying is that we can learn how to relate to our desires and aversions more skillfully, rather than being mindlessly led around by them. And that is the only path to true freedom and living a fulfilling life of integrity, wisdom, and joy, and a life that is in alignment with our innermost and highest values.

Rhonda, one of my meditation teachers back in Pittsburgh, used to liken it to commuting on a familiar route. Taking the main highway might require the least mental effort, but it might not be the best, fastest, safest, or most pleasant route. The only way to know is to cultivate the ability to choose something different: something other than what comes to mind automatically.

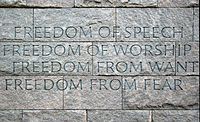

Then she would describe her commute home on Ohio River Boulevard. She could stay on the highway, but the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation had thoughtfully placed a big traffic sign indicating (the town of) “Freedom” with an arrow indicating the off-ramp (that’s it, above). True freedom is exactly that kind of off-ramp, giving us an opportunity to get off the limited access highway of compulsive reactivity and mindless habit.

If you want to be truly free – not satisfied with the mere illusion of freedom and the suffering that it entails — you need to be able to see beyond desire and aversion, beyond reactivity and habit. Freedom means being fully awake in every single moment, willing and able to make real, meaningful choices that are informed by one’s ethical values.

The key to success is developing the skill to be awake enough in each moment to avail ourselves of that little window in the chain of dependent arising, where our perceptions of pleasure and discomfort, if unexamined, can blossom into untempered desire and aversion. If you will excuse me hyper-extending an apocryphal truth: in terms of manifesting wisdom and living an ethical life, the price of freedom is eternal mindfulness.

Or so it seems to me.